Now I know the first time I wrote about my Model M keyboard I said it wasn’t worth it to leave a $10 dev board attached to the keyboard, opting instead to use an adapter, but I’ve changed my mind. My change of heart came about for two reasons:

- I couldn’t get the $5 adapter to work.

- Being able to remap keys on the fly is definitely worth $5.

That second point is in reference to my recent blog post.

I found it easier to get my own IBM Model M to USB adapter working,

this time opting to use a Trinket M0 CircuitPython board.

By using the little CircuitPython board, I can edit a mapping.py

file whenever I want to change what each key on the Model M does.

Getting it to work wasn’t very easy. It turns out that just bit-banging the PS/2 protocol that the keyboard uses, while very feasible in C, does not work out too well in python. For each keypress, I would process just two clock pulses, out of the eleven (start and stop bits, parity bit, eight data bits).

My next thought was to use SPI. Since it is implemented in hardware, it would definitely be fast enough to read PS/2, and they seemed similar enough that I could get it all to work. Except CircuitPython doesn’t seem to support SPI slave mode yet. Oh well, on to the next idea.

I then figured, “I know I can read PS/2 from an MSP430, I should just use one of cheaper chips and have it send key state information over UART to the Trinket M0!”

As it turns out, this thought cost me a few hours, as for some reason I was unable to get Energia working. I tried two different launchpads, two different operating systems (Windows and Linux), and three different energia versions. I tried a few fixes from various sources online, tried reinstalling drivers, playing with settings, everything I could think of. I’m not sure what is happening there, as I used those boards plenty of times in the past, and they do appear as COM ports in both Windows and Linux. I could have tried using Code Composer Studio, but didn’t feel like downloading it again.

I then noticed that CircuitPython has a module for reading in pulse-widths. That seemed pretty useful - assuming the line isn’t too noisy, it seems that a list of pulse widths would have a bijective mapping to the keyboard scancodes, as I would think it is just a form of Run-length encoding.

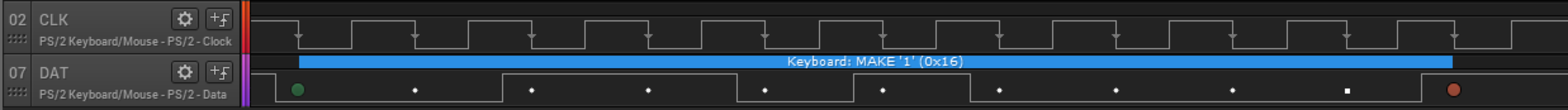

Basically, as soon as the CLK line goes low, I start reading in pulses

on the DAT line. After a few milliseconds, I check the pulses I read.

I read the pulses into a tuple, which might look something like

(2, 1, 1, 4). Because PS2 idles with the DAT line high, I have

the pulseio module start tracking when the line is low. It seems

to skip the first low pulse - I’m not sure if that is because I’m

reacting too slowly, or if that’s just how pulseio works.

In any case, looking at the example from earlier, (2, 1, 1, 4), this

means after an initial low pulse, there is a high pulse of two clock

cycles, followed by a pulse of one clock cycle, followed by a high

pulse of one clock cycle, followed by a low pulse of four clock

cycles. Because there are a fixed number of clock cycles in each

PS/2 message, 11, we can figure out what the initial low pulse was.

We don’t need to, though, as we have enough information to uniquely

identify the key.

If, for whatever reason, we did want the scan code, it isn’t hard

to figure out.

Working backwards, we know the scancode ends in four zeros, then

has a one, then a zero, then two ones, making it 11010000.

We know that last 0 is the parity bit, and we know that the sequence

starts low, so the new missing bit is filled in with a 0 after

everything is shifted to the right one. This gives us 01101000.

Now, PS/2 sends its data least significant bit first rather than

most significant bit first, so we flip our number around to get

00010110, or 0x16, the scancode for the 1 key.

So, I defined a python dictionary to map those tuples to USB keycodes.

I did this in a separate mapping.py file, so the key mappings

can be changed without having to worry about changing the logic

of the board accidentally.

Anyways, I’m not quite done mapping every key, and a downside of how I did this is that I can’t send commands to the keyboard reliably, so I can’t have the keyboard change scancode sets. This is a problem as I can’t detect key presses and key releases for non-modifier keys. I plan on implementing the PS/2 communication in C and adding it to a fork of CircuitPython, but that might have to wait.

The current code is available in my blog work repo.